This is the original, correct version of the piece that appeared in the print edition of The Globe and Mail missing a paragraph.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization—better known as NATO—was originally founded in 1949, as the first Secretary General Lord Ismay famously put it, “to keep the Soviet Union out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.” Since then it has grown from 12 to 29 members and is universally considered the most successful military alliance in history.

What makes NATO so successful is that it is much more than a military alliance. It is a club of like-minded states, as the preamble to the North Atlantic Treaty puts it, “determined to safeguard the freedom, common heritage and civilisation of their peoples, founded on the principles of democracy, individual liberty and the rule of law.” These shared commitments have socialized its members profoundly over the years to identify with each other, cementing bonds of solidarity and reinforcing what are, historically speaking, unusually robust norms of peaceful dispute resolution. Together with the European Union, NATO must get credit for solving “the Franco-German problem,” eliminating war in most of Europe, and creating what political scientists call a “security community”—a region in which the threat or use of force has truly become unthinkable.

But there is an odd man out.

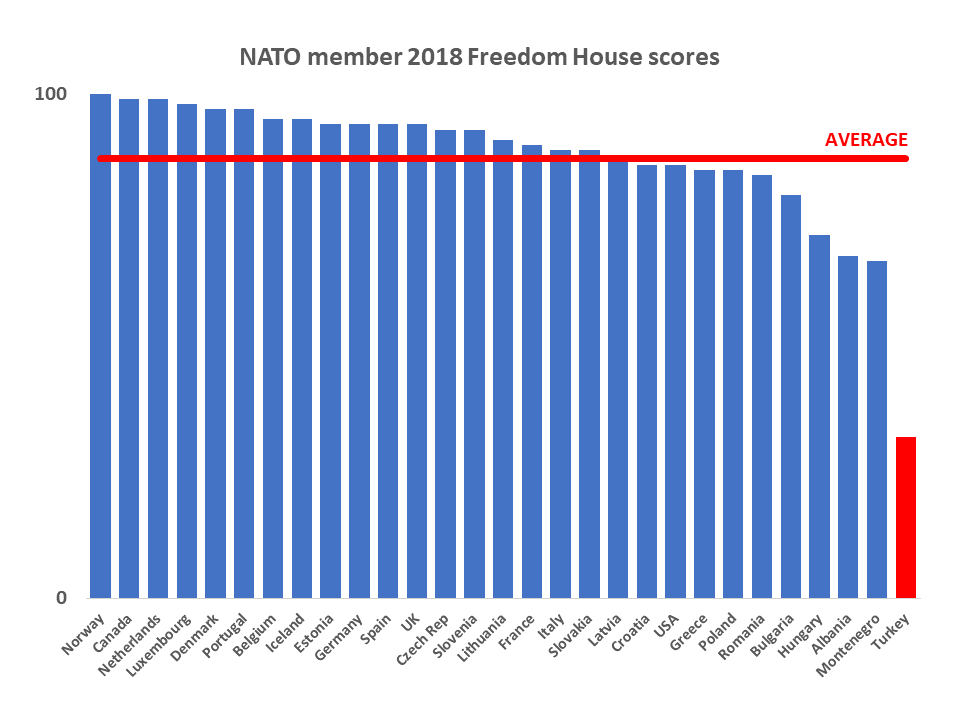

In its latest “Freedom in the World” report, Freedom House dropped Turkey from the “partly free” to the “not free” category, citing President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s “growing contempt for political rights and civil liberties in recent years” and “serious abuses in areas including minority rights, free expression, associational rights, corruption, and the rule of law.” With an aggregate score of 32/100, Turkey is a stark outlier in NATO, well behind second-last Montenegro (67) and the overall NATO average (87). Moreover, the trend is bad. Turkey dropped 6 points from 2017, more than any other NATO member, only three of which dropped 3 points or more (Hungary, Poland, and the United States).

While Turkey’s deepening authoritarianism alone should be enough to disqualify it from NATO, its recent behavior is of at least equal concern. While perhaps not overtly complicit with the so-called Islamic State (ISIL) as some have charged, it passively enabled it by failing to seal off the flow of jihadists to, and oil from, ISIL-controlled territory. More recently, it has intervened militarily in Syria for the sole purpose of preventing the most effective anti-ISIL fighting force—the Kurdish YPG, armed and trained by the United States—from consolidating territory along its southern border. Far from contributing to a peaceful solution to the tragic situation in Syria, Ankara is inflaming it.

While Turkey’s deepening authoritarianism alone should be enough to disqualify it from NATO, its recent behavior is of at least equal concern. While perhaps not overtly complicit with the so-called Islamic State (ISIL) as some have charged, it passively enabled it by failing to seal off the flow of jihadists to, and oil from, ISIL-controlled territory. More recently, it has intervened militarily in Syria for the sole purpose of preventing the most effective anti-ISIL fighting force—the Kurdish YPG, armed and trained by the United States—from consolidating territory along its southern border. Far from contributing to a peaceful solution to the tragic situation in Syria, Ankara is inflaming it.

In 2017, Turkey also broke ranks by purchasing an advanced Russian surface-to-air missile system, the S‑400, over strong objections from fellow NATO countries. The deal not only benefits NATO’s chief strategic competitor but threatens to undermine the interoperability on which NATO’s military effectiveness depends.

It is possible, of course, that a future Turkish leader will right the ship and bring Turkey back to the fold. Erdogan himself is entirely to blame. Fifteen years of increasingly authoritarian rule have shown once again the wisdom of Lord Acton, who wrote, “Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” But apparently healthy, only 64, and through his own political machinations essentially President for Life, Erdogan could be around for a long while yet.

There are two practical obstacles to pushing Turkey out of NATO. One is the North Atlantic Treaty itself, which provides for accession but not expulsion. All decisions of the NATO Council are by unanimous consent, so Turkey wields a veto. One would have to rely upon Erdogan’s sense of shame to induce him to withdraw.

The other is that Turkey holds a metaphorical gun to Europe’s head. In 2016, Turkey and the EU concluded an agreement by which Ankara agreed to take in “irregular migrants” trying to make their way from Syria to Europe in return for material and financial support for resettling them in Turkey and liberalized visa processing for Turkish nationals. With more than 3 million refugees in Turkey, Erdogan could conceivably, in a fit of pique, unleash a human torrent upon Europe that would make the 1980 Mariel Boatlift look like child’s play.

At the end of the day, Turkey’s fellow NATO members may not—probably will not—bite the bullet and try to maintain the integrity of the club. But they should at least make clear that Turkey is now a member only by forbearance, not by desert.