“Trump or taxes?” That is the question people inevitably ask when I say that I relinquished my U.S. citizenship. The answer is neither.

[This piece was originally published in The Globe and Mail, November 25, 2018.]

I was born in the United States, which, according to the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, automatically made me an American citizen. My mother was from Canada, however, and shortly after my American father died, she moved us back to Canada. I was 11 years old.

One day the following year my mother came home and said, “Congratulations, David, you’re a Canadian now! Here’s your new passport.” I did not know why I was suddenly Canadian. Did my mother go through some kind of naturalization process on my behalf, because I was a legal minor? Was I always entitled to Canadian citizenship because she was Canadian? I had no idea.[1] All I know is that at that time I believed that getting a Canadian passport meant that I was no longer a U.S. citizen.

Apparently, a lot of American officials agreed. After I completed my bachelor’s degree at the University of Toronto, I applied to graduate school at Harvard as a foreign student. I crossed the U.S. border on my Canadian passport with an F1 International Student Visa. I remember the immigration officer giving me a stern lecture. “Don’t even think of working off campus,” he said. “For that, foreigners need a Green Card.” (Shortly after I arrived at Harvard, I approached the International Students’ Society to inquire about joining. They looked at me, dumbfounded. “Where are you from?” they asked. “I’m from Canada,” I said. They burst out laughing: “This is the international students’ society!” But that is a subject for a different essay.)

I had been at Harvard for four years when one day my mother rang me on the telephone:

“Hello?”

“Sit down, David.”

“Why?”

“I have some news.”

“What?”

“You’re still an American.”

I was gobsmacked. How could I possibly be an American? I had an F1 International Student Visa—issued by the U.S. Department of State, no less.

It turns out that my mother had learned through a friend that several years earlier a U.S. Supreme Court decision held that acquiring a second citizenship was, by itself, insufficient for expatriation.[2] “In establishing loss of citizenship,” the Court declared, “the Government must prove an intent to surrender United States citizenship, not just the voluntary commission of an expatriating act such as swearing allegiance to a foreign nation.”[3] Put another way: if you wanted to give up your American citizenship, you had to make that absolutely clear through an official act of renunciation—which I had not done.

I went home to Ottawa for the holidays shortly thereafter, and on my way back to Cambridge, I stopped in the office at the U.S. border crossing and asked whether I was, in fact, still an American. The desk officer said he did not know, so he called over some colleagues. They scratched their heads; they did not know either. They called their supervisor. He pondered for a while and said, “Why not apply for a U.S. passport? If you get one, that must mean you’re an American.”

I did, and I did. I felt a little thrill, like I had beaten the system. I now had the right to come and go at will. I had the right to live and work in the United States if I so chose. I had the right to vote in two countries. It was a bit like suddenly having twice as many perks. But something wasn’t right: if I was still an American, why didn’t I feel like an American?

As I child, I had felt very much like an American. I had had the proverbial full patriotic education. Every morning in elementary school we pledged allegiance to the wall. Every day our teachers told us that we were the Luckiest People on Earth to be citizens of the Greatest Country on Earth. I had Canadian relatives, of course, and I loved them dearly, but Canada was strangely different—particularly Montreal, where my grandparents lived. I couldn’t understand what half the people there said. Once, when I was six years old, I made the mistake of turning to my mother in a crowded restaurant filled with francophones and asking in an overly-loud voice, “Why aren’t these people speaking properly?”

Not surprisingly, as a good little American, my sense of existential dislocation was overwhelming when we first moved to Canada. To some extent I brought this upon myself.

I vividly remember opening day of Grade 6 history class in my new school. The teacher began by asking, “Does anyone know who won the War of 1812?” That was easy, I thought. That was the last topic we had covered in Grade 5 history back home.

“The Americans won,” I said.

Stunned silence. Then mayhem.

“You idiot!” my classmates roared; “CANADA won the War of 1812!”

I tried to defend myself. My Grade 5 teacher had taught us that the British had never reconciled themselves to U.S. independence and were trying to strangle the new country economically, but American troops marched on Canada and forced Britain to back down. My Canadian classmates countered that the Americans were trying to conquer Canada and were bravely thrown back. My Grade 6 teacher sat back and watched—smiling—as a beautiful, utterly unplanned lesson in historical relativism unfolded before his very eyes. He and I eventually became good friends.

For two years, I was mocked and bullied, not only for my historical heresy, but also for my strange accent. Every time I said “AD-ver-tise-ment,” my classmates would pounce: “It’s ‘ad-VER-tise-ment,’ you bloody Yankee!” They laughed when my writing assignments came back covered with red ink for misspelling “labour” as “labor,” or “centre” as “center.” Even my Headmaster mocked me. He would go out of his way to make me say the word “falcon” just so that he could correct me: “It’s FAWL-con, not FAAL-con!” He always giggled. We eventually became good friends, too.

The turning point came in 1972, during the Summit Series between the Soviet men’s national hockey team and Team Canada. The series was, of course, a proxy for the Cold War, and global bragging rights for moral and athletic superiority were on the line.[4] When the Soviets trounced Canada 7–3 in Game One in Montreal, the entire school—nay, the entire country—went into shock. Canada came back to win Game Two in Toronto, and the two teams tied Game Three in Winnipeg, but the Soviets handily won Game Four in Vancouver, and it was with the weight of the country’s pride on their shoulders that Team Canada boarded the plane for the final four games in Moscow, down two games to one.

The Soviets won Game Five, but Canada stormed back to win the next two games. With overall victory on the line in Game Eight, our Headmaster cancelled classes, and we all huddled around the television set in the common room in trepidation. The game was tight. For two periods the Soviets dominated, but in the third period Team Canada tied the score, and with 34 seconds left, Paul Henderson buried the winner behind Soviet goalkeeper Vladislav Tretiak. The room exploded with euphoria, everyone sang O Canada!, and I knew for the first time that I. Was. Canadian.

Stockholm Syndrome may be an inauspicious beginning for a new national identity, but I never looked back. I have felt Canadian—and only Canadian—since that day. By that point my mother had already told me that I had Canadian citizenship, so that was the first moment since moving to Canada that I felt the universe properly ordered. When I learned 15 years later that I had actually been an American all along, something seemed off.

The three elements of citizenship

I spent quite a lot of time trying to understand my discomfort with my dual citizenship. I am ashamed to say that the convenience of having two passports kept my introspection in check. But to some extent the thought that I was technically a dual citizen inclined me to try to overcome my unease. So it was with relatively little discomfort that I took on greater civic engagement in my latter years at Harvard. I became actively involved, for example, in Michael Dukakis’s 1988 presidential campaign, where my role was to teach Mike everything he would ever know—and never need to know—about nuclear weapons.

I moved back to Canada in July 1990, when I took up a teaching position at my alma mater. Civic engagement now meant Canadian civic engagement, so my latent angst about having dual citizenship largely faded. Identities are only activated when they are salient, and most of the time my American citizenship was simply irrelevant. When I traveled abroad, for example, I would always travel on my Canadian passport.

The angst only surfaced when I travelled to the United States, because, under U.S. law, if you have an American passport, you must use it to enter the country. I got into the habit, however, of writing “Canada/USA” on the U.S. customs and immigration form where it asked for my citizenship.

One day I encountered a particularly nasty U.S. immigration official who looked at my form and snarled, “Which citizenship are you claiming today?”

“I have two citizenships,” I replied.

“No, you don’t,” he said, taking a red marker and striking “Canada” from my form. “I bet you’ve been to Cuba, too!”[5]

I knew he was wrong. At that time, the United States did not acknowledge dual citizenship, but neither did it care if one had it. All Washington cared about was whether you were a U.S. citizen. But I could tell that this was an argument I was not going to win. I also had enough sense not to say, “Yes, in fact, I have been to Cuba, several times. I even spent four days in the same room with Fidel in Havana, twice.” I simply said nothing and moved along. But there are no words to describe the anger and disgust I felt at this petty authoritarian bureaucrat denying my identity and treating me like some kind of traitor for deigning to affirm my Canadian citizenship.

This unsettling experience concentrated my mind anew. Here was an official from one of the two countries to which I ostensibly belonged essentially treating me as an outlaw and moral inferior simply for having two passports. He was ignorant and hateful and I wanted to smite him. And yet I shared his discomfort with dual citizenship.

Ultimately, I realized that my discomfort lay in my understanding of citizenship as such—as a form of membership in a political community that carries with it three distinct sets of things: (1) rights; (2) benefits; and (3) obligations. Rights include, for example, entry and domicile, and, in a liberal democratic country, to vote, to run for political office, and not to be incarcerated without due process of law. Benefits might include such things as preferential access to government services, dedicated international arrivals screening counters at airports, and eligibility for national grants, fellowships, or loans. Obligations would include loyalty, obeying the law, paying taxes, and—if called upon—service in defence of the state.

Dual citizenship poses no difficulty to the enjoyment of rights and benefits. The more, the better. If citizenship were only about rights and benefits, we would all be foolish not to collect as many passports as we possibly can.

The difficulty is with obligations. It is here that citizens must seriously entertain the idea that they must make efforts—and occasionally make sacrifices—for the countries to which they belong. On rare occasions, these obligations might include putting one’s life on the line. Obligations are the quid pro quo for rights and benefits. Having dual citizenship means that you could, in principle, be called upon to serve in the armed forces of both of your countries at the same time. They might even go to war with one another. In such a case, you would have no choice but to be a traitor to at least one of your countries. This is exactly what happened in 1812. In the early 19th century, Britain did not recognize naturalized U.S. citizenship and considered anyone born a British subject to be a British subject for life. Accordingly, it felt no compunction against boarding American ships and “impressing” some 9,000 American sailors into service with the Royal Navy.

Whatever else citizenship means, it means owing primary political loyalty to the state to which you belong. You cannot owe primary political loyalty to two or more states. This is the essence of the paradox of dual citizenship.

When I first began articulating this view, there was more than one awkward moment with family or friends who also had two passports and clearly had no intention of giving one of them up. No one challenged the paradox directly. Some simply said honestly that the convenience of having two passports was irresistible. Others objected that the idea of their two countries going to war was preposterous. This is certainly true in the case of the United States and Canada today, but it is also beside the point: something being empirically unlikely does not make it logically impossible. The paradox is a matter of principle, not (necessarily) empirics. In any case, the United States and Canada may not go to war again, but they are constantly facing off for Olympic hockey gold. There is something profoundly wrong about cheering against your own country’s national team. Call it postmodern treason.

Interestingly, philosophical debates about citizenship essentially ignore the paradox. They focus on the one-to-one relationship between the citizen and the state. They shine the spotlight on such issues as the legal rights attending citizenship, the participatory requirements of citizenship, the challenges that globalization and mobility pose to some ideal “fit” between citizenship and territoriality, the gendered construction of citizenship and its supposed reliance on a stark public/private distinction, or the tension between a cosmopolitan conception of human rights and the exclusive claims of states to regulate their own affairs according to their own values, norms, and traditions. These are all interesting issues, but they dodge the central question here: What should someone do when their countries make conflicting claims upon them?

Practical problems for both citizens and states

Logical paradox is not the only problem with dual citizenship. It poses a range of practical problems for individuals and states alike. For example, American citizens abroad must file U.S. income tax returns. While the United States has treaties with many countries to prevent double taxation, American tax forms are extremely complicated and most dual citizens pay exorbitant fees to accountants or lawyers every year simply to file them—even if they owe no tax. Moreover, differences between (for example) U.S. and Canadian tax codes mean that Canadian citizens who also have U.S. citizenship are exposed to certain liabilities that their non-hyphenated Canadian compatriots do not have—for example, estate taxes and taxes on lottery winnings. Recent changes in U.S. tax law have put at risk the retirement plans of thousands of Canadians who incorporated under Canadian law to benefit from lower tax rates, only now to find themselves exposed to new, draconian American taxes. In fact, escaping onerous tax-related liabilities is the number one reason more and more Canadians are renouncing their U.S. citizenship every year. I am a rare exception: I am not wealthy enough for this to be a problem, and I always file my own taxes.

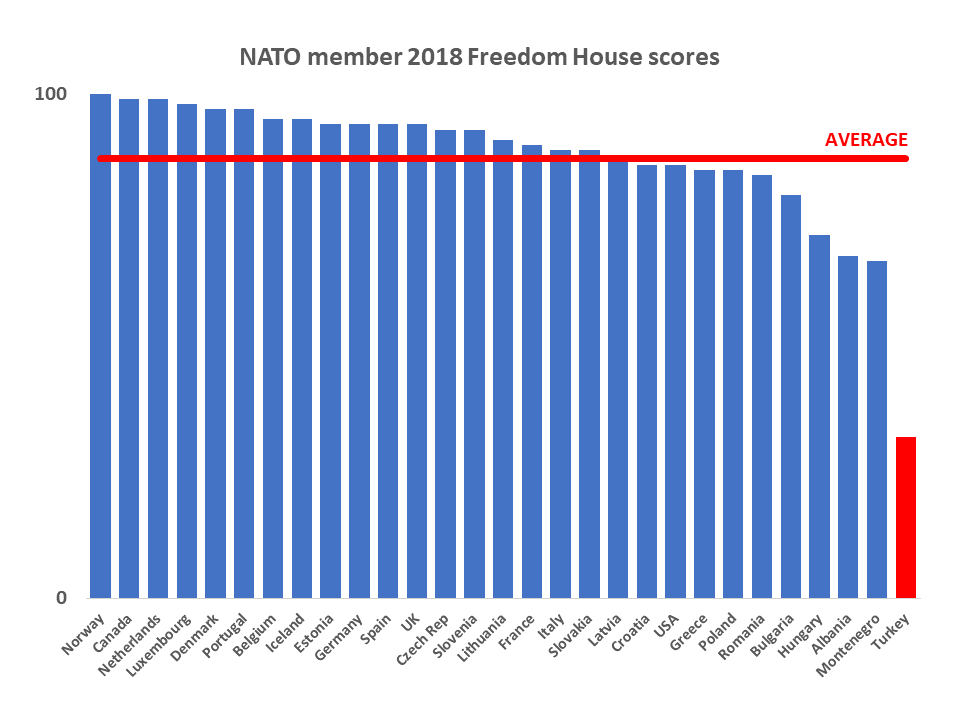

Dual citizens can also find themselves in jeopardy unexpectedly. Once upon a time, I narrowly escaped a Turkish prison. When I was 16, I signed up for an educational cruise to the eastern Mediterranean. We docked in the port of Izmir, where I was listed on the ship’s manifest as “D. Welch.” The Turkish military police marched aboard and demanded that I be handed over for military service. I was a Turkish citizen, they insisted, and had missed my reporting deadline. It turned out to be a case of mistaken identity: my elder brother—also a “D. Welch”—was born in Turkey, on a U.S. Air Force base. He had no idea that Turkey considered him a citizen. It was sheer good luck that I, rather than he, had signed up for the cruise.

States, too, can find themselves in difficult situations because of dual citizenship. A rather infamous case concerns Zahra Kazemi, an Iranian-Canadian freelance photographer who travelled to Iran in 2003 on her Iranian passport, was wrongly arrested for spying, jailed, tortured, sexually assaulted, and beaten to death by Iranian authorities. The Iranian government, not recognizing dual citizenship, refused Kazemi Canadian consular assistance, causing a major rift in Canada-Iran relations. Another Canadian citizen, Huseyin Celil, an ethnic Uyghur from Xinjiang, languishes today in a Chinese jail without access to consular assistance because China does not recognize his Canadian citizenship. The case continues to strain Sino-Canadian relations.

More recently, dual citizenship caused a major political crisis in Australia, whose constitution provides that anyone “under any acknowledgement of allegiance, obedience, or adherence to a foreign power,” or who is “a subject or a citizen or entitled to the rights or privileges of a subject or citizen of a foreign power… shall be incapable of being chosen or of sitting as a senator or a member of the House of Representatives.” It turns out that several sitting Australian parliamentarians had dual citizenship either by birth or descent, five of whom claimed to be unaware of it. The courts ruled ten ineligible, briefly causing Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull to lose his lower house majority.

Dual citizenship has benefits, of course, including consular protection when states recognize it. But in cases where dual citizenship causes people or states trouble, the root cause is the simple fact that sovereign states determine their own citizenship rules and decide for themselves whether to acknowledge dual (or multiple) nationality. It stands to reason that in a globalizing world where mobility is on the increase, we should expect this cacophony of citizenship rules to cause more and more problems.

There are two possible solutions.

First, the international community could ban dual citizenship. Everyone would be expected to have one and only one. It is difficult to imagine how this could be done without convincing all states to agree to a single overarching eligibility rule to avoid conflicting claims on people’s loyalty. The simplest and least complicated would be jus soli, the principle of determining citizenship by place of birth. Alternatively, states might agree to allow people to decide for themselves to which state they will owe primary political allegiance. Since many people today carry two passports without the knowledge of at least one of the issuing countries, this would also require establishing an international registry in which to record, and against which to check, everyone’s citizenship.

It is difficult to imagine states being enthusiastic about this. Forcing states to agree to a shared citizenship criterion would represent an unprecedented qualification of sovereign prerogative. Allowing people to choose their own citizenship willy-nilly would also undermine states’ abilities to redeem citizens’ obligations in time of need. In many cultures, both options would run against the grain of deeply-entrenched views of political community as founded on blood ties (jus sanguinis).

It is difficult to imagine many current dual nationals agreeing to this, either. Few people voluntarily give up rights and benefits. Those who would like to give up one of their citizenships can usually do it if they feel strongly enough, though, in some cases—most notoriously, in the case of the United States—the process is time-consuming and fantastically expensive. Certainly the idea of an internationally-accessible citizenship register would also raise privacy alarms. It would almost certainly be inconsistent with current European Union privacy laws, for example.

A second possible solution is for states to agree on an internationally recognized second-tier affiliation status. Everyone would be expected to owe primary allegiance to one state, but could enjoy another state’s rights and benefits, and be subject to its obligations, except when they conflict with first-tier citizenship obligations. The obstacles to this arrangement are precisely of the same kind as to the first, though perhaps of lesser magnitude.

It is difficult to see a path forward. With states jealously guarding their sovereign prerogatives and people increasingly keen to secure more than one passport, either for reasons of convenience or because they feel a genuine attachment to more than one country, we are likely stuck with the current cacophony of citizenship rules, and without some arrangement addressing the problem of double jeopardy, painful conflicts will be inevitable.

Citizenship, attachment, and identity

Some will object that my own tale betrays a glaring gap in my argument against dual citizenship: namely, its failure to take into consideration the powerful role that citizenship plays in shaping one’s identity. A sense of belonging to community is, for most people, a basic psychological need, and disrupting the bonds between a citizen and his or her state comes only at high emotional cost. I experienced this myself. My first two years in Canada were extremely painful. I was plucked from my country of origin, forcibly exiled to another, and summarily informed that I was no longer who I was but was now someone else instead.

In the ideal world, there would be no misfit between citizenship and affective attachment. It is perfectly possible for someone to identify with two countries and to feel a powerful sense of belonging to both. What is wrong with dual citizenship, in such a case?

Part of my response would be that even a sincere and powerful sense of attachment does not eliminate the paradox. One could still in principle be forced to be a traitor to at least one of one’s countries. But more fundamentally: people don’t get to choose their citizenship(s). States decide. That’s simply how it works. From a liberal, cosmopolitan perspective, this may seem arbitrary and unjust—but we do not live in a cosmopolis. For better or worse, the world is carved up into sovereign, territorial communities akin to clubs. States themselves are members of a club: to be recognized as a state, a state must be acknowledged to be one by other members. Similarly, to be a citizen, one must be acknowledged to be a citizen by a state. No one has a right to be a member of a political community just because they feel a strong attachment to it. Were it to be otherwise, I would have a right to demand Japanese citizenship.

Still, affective attachment can be powerfully diagnostic. It can help guide you when you have political choices to make. I expect that if I still felt after all these years that being American was central to my sense of self, I would have had a much harder time deciding whether to give up my U.S. citizenship. In conflicts between the heart and the head, the head does not always win. But neither should the head refuse to acknowledge a paradox just because the heart does not wish to confront it.

[1] I have since learned that, under Canadian law at the time, my mother was entitled to register my Canadian citizenship because she herself was Canadian—but only because my father had died, making her the “responsible parent.”

[2] Vance v. Terrazas, 444 U.S. 252 (1980).

[3] Id. at 252.

[4] See, e.g., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WPzaVDilFEI.

[5] U.S. border officials commonly mistakenly believe that U.S. citizens are prohibited from visiting Cuba. This is incorrect. Under the terms of the U.S. embargo, they are not allowed to spend U.S. dollars in Cuba—and even here there are six categories of exemptions, one of which is academic research.